Prejudiced Protests

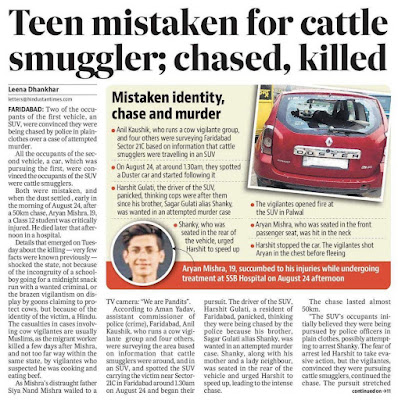

In my previous post, I tried to discuss my concerns about the law and order situation in India. Unfortunately, as is often the case, new incidents keep cropping up that force me to think again about the state of affairs. One such incident involves the tragic case of Aryan Mishra, a 19-year-old boy shot to death by a group of cow vigilantes who claim it was a "mistake."

This case has sparked an outpouring of outrage. As I read the discourse surrounding this incident, something deeply troubling emerged. The accused, after confessing to their crime, expressed guilt not over the act of taking a life but over the fact that they had mistakenly killed a Brahmin boy. It's as if the entire tragedy would have been shrugged off had the victim belonged to a different caste, perhaps a lower one. This confession brings to light an uncomfortable truth about how our society values human life – not equally, but based on the arbitrary lines of caste and religion.

Think about this for a moment: A similar incident occurred not too long ago when a mob lynched a Muslim man on the suspicion that he was eating beef. As it turned out, he wasn’t even eating beef; he was eating chicken. But where was the outrage for him? Did the accused, or anyone else, lose sleep over the senseless loss of his life? No. But when it comes to Aryan, a Brahmin, even the murderers feel remorse. Is this the kind of society we have become?

The facts of the Aryan Mishra case are both chilling and tragically common. Aryan, along with his friends, set out on what should have been a simple late-night drive, only to be chased by a group of self-appointed cow protectors. This chase led to his brutal killing. And now, days later, here we are, once again, dissecting not just the crime but the selective outrage it has generated.

This is where I get stuck. How did we get here? Why is our collective sense of outrage so fickle, so dependent on the caste or religion of the victim? Why do we, as a society, seem more invested in certain lives than others?

In Aryan’s case, the accused were quick to point out their regret after learning his caste. It’s as if the mere discovery that he wasn’t a Muslim made them rethink the value of his life. What does this say about us? Do we really need to know a person's caste or religion before deciding whether to feel outrage? It seems so.

But let’s not pretend that this is just about the accused. The reaction of the wider public, too, has been baffling. A Brahmin boy gets killed, and suddenly we see protests, public outcry, demands for justice. Compare this to the relative silence that follows when lower caste individuals or Muslims face similar fates. When they’re killed, the air is thick with indifference. What does that say about us as a society?

We like to think of ourselves as a democracy, a nation that values justice and equality. Yet, when it comes to public reactions, the truth is much uglier. It’s as though we carry some invisible scale where the weight of outrage depends not on the crime but on who the victim is.

Look at the pattern. The recent lynchings of Muslims over beef suspicions hardly caused a ripple. Meanwhile, the death of Aryan Mishra has sparked protests and legal action. There’s no doubt that Aryan’s death is tragic and deserving of justice, but I can’t help but wonder: where is the justice for the others? Why does it take a Brahmin victim for society to wake up?

I understand that life in India, for many, feels like it has little value. I understand that our law and order system is deeply flawed. I understand that the loss of a child is a traumatic event for any family. What I don’t understand is how people can so selectively choose their battles, their protests, and their outrage. Why do we need to check someone's caste or religion before deciding whether their death is worth caring about?

This raises a fundamental question: What is our outrage really about? Is it about justice? Or is it simply about identity?

There’s another layer to this that disturbs me. The cow vigilantes involved in Aryan’s death weren’t rogue criminals. They were part of a larger system of self-righteous, self-appointed enforcers of morality – in this case, so-called "cow protectors." But their sense of protection seems to only extend to certain animals and certain people. How do we allow this vigilantism to continue in a society that claims to be governed by the rule of law? Why are we okay with people taking the law into their own hands when it suits a particular ideology?

And then, of course, there’s the ultimate irony: the people who killed Aryan Mishra claim they did so because they thought he was a cattle smuggler. Does that justify murder? Would it make his death any less tragic if he had been a Muslim or a Dalit? Why is it that the very people who cry foul over cattle slaughter seem to value human life so cheaply?

At the core of this issue lies a deeper rot – one that we, as a society, need to confront. It’s the rot of selective empathy, of valuing lives differently based on arbitrary markers like caste and religion. It’s the rot of assuming that some lives are worth more than others, that some deaths are worthy of outrage and others are not.

I am left wondering, as I often do, how we reconcile this. How do we stand as a nation and claim to value human rights when the very basis of our reactions to injustice is so deeply flawed? If we want to live in a just society, we must first address the biases within us. We must be as outraged at the death of a poor Muslim man as we are at the death of a Brahmin boy. We must hold accountable not just the vigilantes who pull the trigger but the society that turns a blind eye to the deaths it finds inconvenient to care about.

What does it say about us that even murderers feel bad – but only when the victim fits a certain profile?

So, I ask you, those of you reading this: Why are Indians so obsessed with caste and religion? Why does justice seem to have caste-based conditions attached to it? And if you think you have a simple answer, I challenge you to explain it to me. Because from where I’m standing, the situation is anything but simple.

Comments